Sourcing strategies developed over 30 years ago hamper innovation and cause value leakage says Kate Vitasek, an author, educator and architect of the Vested business model. Instead of relying on static "best practices," she advocates considering one of the seven Sourcing Business Model Theory approaches to find a model that fits your business situation.

Learn more about Kate Vitasek and her role as a SIG University Faculty Member.

When a company seeks a strategic supplier, the crucial first step is to choose the right sourcing model, which will make or break the relationship. Unfortunately, many organizations are not operating with sourcing strategies: they are anchored in buying strategies developed more than 30 years ago.

Take for example the Kraljic matrix introduced in 1983 by McKinsey consultant Peter Kraljic in the classic 1983 Harvard Business Review article “Purchasing Must Become Supply Management.” Kraljc suggested buyers categorize purchases across two dimensions — profit impact and risk. To help organizations simplify the approach, he devised a quadrant “matrix,” an instant hit due to its simplicity. Today, many consider the Kraljic matrix the standard purchasing portfolio management model.

Once the spend categories were classified, Kraljic suggested a buying organization’s next step was to “weight the bargaining power of its suppliers against its own strength as a customer.” Based on an organization’s power relative to its supplier, he notes, there are three primary purchasing strategies: exploit (in the case of buyer dominance), balance (in the case of a balanced relationship) and diversify (in the case of supplier dominance).

Kraljic suggested the “exploit” strategy was the preferred approach and encouraged buying organizations use their power to reduce supply risk and get the best price by using your power – whether by consolidating volumes or simply by using their market clout through competitive bids.

Caveats of Best Practices

Another example is the “best practice” of using a “seven-step” sourcing process. The process – made popular by AT Kearney – now has many variations ranging from five to 11 steps. Regardless which method you use, there is a weakness because applying a “best practice” sourcing process could easily be overkill for many things organizations buy.

Second, while many sourcing initiatives are one-time projects from “needs” to “disposal,” there is tremendous opportunity to create value before and after the sourcing cycle. This is especially true (1) for direct-spend items, where early supplier involvement in design can yield significant value; and (2) in outsourcing relationships that demand ongoing, more collaborative supplier relationships.

Research shows that as much as 70% of the cost impact of a spend category is determined at the product- or service-design stage. Consider: If a buyer is asked to purchase a category after design, that buyer can address only 30% of the cost, inhibiting the ability to meet cost-reduction targets. Third, many sourcing initiatives like complex outsourcing contracts are not “one and done.” Instead, they require ongoing collaboration and governance, and there is no “disposal” aspect – but rather an ongoing evolution and demand for innovation over the duration of the outsourcing contract.

The Weaknesses of Conventional Strategies

While these older strategies “work” to a degree, they are not as effective in today’s environment that is more global, more complex and more dynamic than ever before. Why? Nearly all supplier contracts today are anchored in a transaction-based economic approaches. This creates a transitional “buy-sell” contract structure and economic model underpinning supplier relationships (for example, cost per unit produced, per warehouse pallet stored, per minute of call center support, or per IT server).

The problem is that the more the supplier sells the more money they make. This is often in direct conflict with the buyer’s goals to reduce their costs. The result? A never-ending battle over price with one party winning at the other party’s expense.

For simple transactions with abundant supply and low complexity, a transactional model is likely the most efficient way to go. But the real weakness of conventional transactional approaches emerges when the business environment is more complex, with variability, mutual dependency, or customized assets or processes. Simply put, a transactional approach cannot produce market-based price equilibrium in variable or multi-dimensional business agreements: other approaches are more appropriate.

But what are these other approaches?

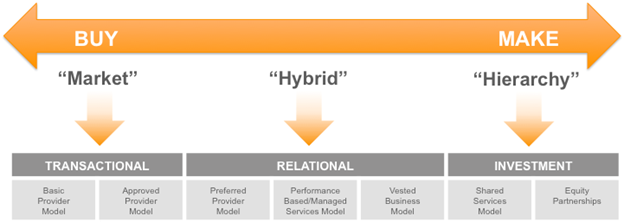

SIG University has adopted the philosophies behind the pioneering work of the University of Tennessee on Sourcing Business Models – using the concepts and the book Strategic Sourcing in the New Economy: Harnessing the Potential of Sourcing Business Models for Modern Procurement to educate today’s sourcing professionals on a continuum that includes seven sourcing business models (see figure below).

Sourcing Business Model theory states that there are seven sourcing business models and it is important to anchor your contract and economic model with your supplier based on the most appropriate model for the business environment.

Basic Provider Model

The Basic Provider Model uses a transaction-based economic model, meaning that it usually has a set price for individual products and services for which there are a wide range of standard market options. This model is used to buy low cost, standardized goods and services in a market where there are many suppliers.

Approved Provider Model

An Approved Provider also uses a transaction-based model with goods and services purchased from suppliers that meet a pre-defined set of qualification characteristics, quality standards, previous proven performance or other selection criteria. Frequently an organization has a limited number of pre-approved suppliers for various categories from which buyers or business units can choose. One firm can easily be replaced with another if the supplier fails to meet performance standards.

Preferred Provider Model

A key difference between the preferred provider and other transaction-based models is that the buyer chooses a more strategic relational approach. Buying companies seek to do business with a preferred provider to streamline their buying process and build longer-term relationships with key suppliers. They often enter into multi-year contracts using a master services agreement that allows them to conduct repeat business efficiently. The preferred provider model is still transactional, but the way the parties work together and efficiencies achieved go beyond the simple purchase order.

Performance-Based/Managed Services Model

A performance-based model is generally a longer-term formal supplier agreement that combines a relational contracting approach with an output-based economic model, based on a supplier’s ability to achieve pre-defined performance parameters or savings targets.

Performance-based agreements shift thinking away from activities to predefined outputs or events. Some companies call the results “outcomes,” but in performance-based agreements the meaning of “outcome” is well-defined as the achievement of an event or deliverable that is typically finite in nature and is therefore easily understood. A good example of an output is a supplier’s ability to achieve pre-defined service level agreements (SLAs).

Vested Business Model

A Vested Sourcing Business Model is highly collaborative: the buyer and supplier have an economic interest in each other’s success. The Vested model combines an outcome-based economic model with the Nobel award-winning concepts of behavioral economics and the principles of shared value – companies enter into highly collaborative, win-win arrangements designed to create value for the buyer and supplier above and beyond the conventional buy-sell economics of a transaction-based agreement.

A Vested business model works best when a company has transformational or innovation objectives that it cannot achieve itself or by using conventional transactional sourcing models.

Shared Services Model

A Shared Services model is an internal organization based on an arms-length outsourcing arrangement. Using this approach, processes are centralized into a “Shared Service” department or organization that charges members for the services used. Organizations use this model for a variety of functional services such as human resources, finance operations and administrative services such as claims processing in health care.

Equity Partnerships

If an organization does not have adequate internal capabilities to acquire mission-critical goods and services, but does not want to outsource or invest in a shared services organization, it may opt to develop an equity partnership. Equity partnerships create a legally binding entity and take a number of different legal forms, from acquisition of a supplier or creation of a subsidiary, to equity-sharing joint venture.

Conclusion

The bottom line? It is your bottom line. Organizations should select the most appropriate Sourcing Business Model for their situation in order to optimize transaction cost economics with more strategic, complex and dependent relationship making the shift up the sourcing continuum to use more modern performance-based and Vested agreements. And – where appropriate – sourcing professionals should be exploring when it makes sense for the company to make investments to shift supply in house.

If you are not investing in educating sourcing professionals you will likely find yourself falling even farther behind in creating value for your organization. Start your learning by treating your organization to the gift of knowledge. You can buy the book Strategic Sourcing in the New Economy on Amazon and enroll in SIG University’s Certified Sourcing Professional program.